The Critical Role of Patient Advocacy Groups in the Development of Rare Disease Gene Therapies

Cell Gene Therapy Insights 2018; 4(7), 733-740.

10.18609/cgti.2018.077

Please can you each tell us about your experiences of getting into Patient Advocacy?

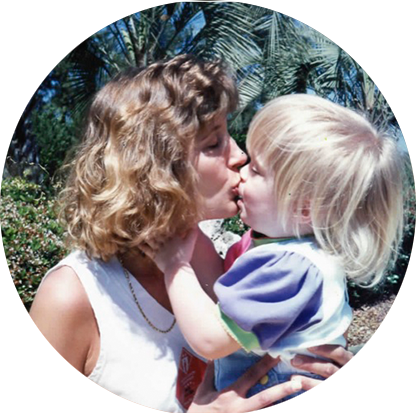

SW: Our foundation was founded because of our daughter Kirby’s diagnosis with Sanfilippo. She was diagnosed at the age of four and at the time (1995) we found no dedicated patient groups or support groups, nor any research. We literally called around the world trying to find doctors currently working on the disease. Ultimately, we found just one: Dr Elizabeth Neufeld at UCLA.

We spoke with Dr Neufeld and asked why there wasn’t more research being done and she explained that even if a doc or post-doc wanted to do this research, if the funds weren’t there, they simply couldn’t. That’s where my own mission, or advocacy, began. I felt we needed to do this because if there’s a chance we can save my daughter’s life and we’re talking $100,000 a year to get this research going, then as a parent, I’m certainly going to try.

Our first goal was to raise awareness within our own community – of the disease, the plight of our daughter, and our mission to find a cure. Beyond that, it was obviously to fund research and in our case, to help expand research into any methodology that held promise at that time.

Again, this was 1995: there was not a lot out there in terms of promising approaches and the internet didn’t exist, so all of our outreach was done through telephone and US mail. Over time, you then learn more and more about the symptoms of the disease and what daily life looks like through caring for your child and speaking to other families. So I guess it started as advocacy for the cure and/or treatment. The actual patient advocacy component grew over time, as we came to understand more about the needs of our child, and how difficult it is to navigate the world with a child with a disability.

EL: Sue and her husband, Brad, were the real pioneers inspiring the efforts that have snowballed over the last 24 years. When my daughter, Elisa, was diagnosed 20 years ago, we talked to doctors who told us to just take our daughter home and enjoy her every day because there was no treatment, no cure, and no real hope of one due to the lack of research funding and therefor research.

We then looked on the internet, found the Wilsons in Chicago and connected with them because we saw they had started something and were raising funds for research.

As a result of meeting them, we were inspired to come back to Canada and do something similar – not least because we had also connected with the MPS society (which is the umbrella society which covers this group of diseases) and they had no budget for Sanfilippo research at that time.

Following us starting The Sanfilippo Children’s Research Foundation, other families in the US initiated more organizations with the same goals in mind. Families worldwide followed and started to get on board as their children were diagnosed and research was moving towards to hopes of clinical trials starting on a potential therapy. We have raised millions of dollars between us and channelled it into research, with the hope of getting some answers – that just led to more and more families getting involved.

That takes us up to around 2013, when groups from around the world started to collaborate as a global network and work together to make gene therapy clinical trials a reality.

Can you tell us more about your fund-raising activities, and how you seek to channel those funds into research, translational R&D and clinical trials?

SW: Our first goal was to include Sanfilippo in all the most promising methods of treatment out there – anything that could hold hope for a genetic disorder. A shotgun approach, if you will. And 25 years ago, this was a whole different story – we’re talking about working to identify and recreate the missing gene and to make a knockout mouse model – so it was very much the basic science we were trying to fund. From around 1995–96, we started to see things like gene therapy, enzyme replacement therapy and stem cells emerging as potential therapeutic options.

I think one thing both Elisabeth and I were successful in doing was trying to include Sanfilippo in all the most promising research that could possibly be appropriate for the disorder – in convincing laboratories to include Sanfilippo in their research projects.

In the early days, my main goal was to fund research to the point where it would reach a level to obtain federal funding. The difference today is while we’re still trying to provide this seed money, smaller biotech companies and venture capitalists are also now becoming interested in the field at these early research stages.

EL: I think a key point to note for both of our organisations is that we are grassroots charities. We are two organisations run solely by volunteers – nobody gets paid for anything. This allowed 96 cents of every dollar we raised, every year for the past 20+ years, to go to research. And I really think that was a key selling point for our charities in terms of garnering support on an ongoing basis.

Yearly we would do the same fundraising activities: marathon runs, garage sales, gala dinners, golf outings and more… And as Sue said, 20 years ago, we would cast a wide net with our research funding. We put $160,000+ a year into research – some towards gene therapy, some for stem cell therapy, then some for small molecule therapy. We would support projects for a year or two until they obtained some initial results, presented papers, and could then submit to other, larger funding agencies in order to get more funds to continue the research. I am happy to say that’s what has eventuated more often than not over the 20 years that we’ve been funding research.

Then we finally reached the stage where one research team in Columbus, Ohio, was at the point of taking their research further and move it to human clinical trials. We needed $5 million plus to do this. It had taken us 10 years to raise that kind of money and now we needed to find it for next year! So we had to really step up our fundraising activities – every year from then on, we took on an additional endeavour to create awareness and raise funds. One year our family organized a climb of Mount Kilimanjaro, another we hiked the Inca Trail in Peru, another year we cycled our bikes around Ireland… We really had to escalate our efforts once the research hit a translational phase. Fortunately, our efforts were successful.

What are your current and future funding priorities and plans which relate to cell & gene therapy specifically? Where do you fell the money is needed most at the moment?

EL: I’m sure you can appreciate that for both of us, 20+ years of caring 24/7 for a child that has special needs while trying to fundraise at the same time has taken a huge toll on our personal lives, our family lives, and on life in general. My daughter passed away at the age of 21, a year and a half ago. It was just after the clinical trials had started for Abeona Therapeutics’ MPS IIIA in Columbus, Ohio, and I was pretty much spent at that point. The last couple of years of Elisa’s life were pretty challenging. And although I did keep all of our fundraising initiatives going, I knew I couldn’t do very much the year when she passed. I’m still trying to determine what the future looks like for our foundation. But what has happened over the last year and a half is there have been more children diagnosed in our immediate community in Toronto, and in Canada in general, and they certainly reach out to me and look to our organisation for support and answers. And they want to do fundraising themselves to contribute to our efforts.

So we are still moving forward – we’re doing what we are capable of doing right now. But we are not raising funds in the same capacity that we have for the last 20 years. We’re not a paid organisation, where we have an executive director who gets paid and works 9–5, 12 months of the year. We will still move forward and will raise what we raise, and we will still continue to support research. But at this point, those funds will go back to seed research grants – almost like how we started out – because the good news is biotechs today don’t need our money to move forward.

One thing our charity did last year was to establish an endowment fund. We granted $1 million to a hospital here in Canada – one that we’ve been sponsoring for almost 20 years – that has a very strong Sanfilippo syndrome research programme. They actually named the lab after our daughter after she passed away. This lab and endowment fund will be our legacy as a foundation in order to keep research going, year after year, without us having to raise the same amount of money that we did in the past. Our plan is to continue to contribute money towards this particular lab at Sainte-Justine Hospital in order to support Sanfilippo research.

SW: Our daughter is still with us, but she’s 27 years old now and the loss of Elisa did set us back in realising how important our time is with Kirby – so my priority has shifted a bit, too, for different reasons. But to add to what Elisabeth said, I would like to see the trials that we are involved with continue. There have been starts and stops in other clinical studies – children receiving a dose of one thing or another, then the trial is stopped for whatever reason.

There are also the children who are immune to the vectors being used, or are simply too old to be considered. My main goal is to find ways for trials to become more inclusive of children who would typically not be included in the protocol. However, I understand that one of the stumbling blocks is that if you have a trial where you might want to include other children, the FDA wouldn’t look at them with separate protocols – they would look on it as a single trial, and it could be detrimental to the data and future of the therapy in question.

So there’s a lot yet to be done in this area that doesn’t necessarily involve funding: my personal goal is to be able to have the opportunity to speak to regulatory agencies about the importance of including more children with various stages of the disease when new trials are beginning.

EL: As I mentioned earlier, there are many family foundations around the world that have emerged and evolved over the last few years, since they heard about the potential of these gene therapy trials. They’re a group of families that have younger children – around 8–10 years of age and younger. And I think I can speak for Sue as well in saying that we feel that, at this point in our lives and journeys, we are ready to pass the baton on to them. They are creating a huge presence in the MPS world and amongst social media worldwide, and they are raising money now themselves. But we’re still working with them. After all, it was maybe 12–15 foundations that united together with our financial resources to start Abeona Therapeutics – the company running the gene therapy trial we discussed earlier. We wanted to create a company together that had the potential to attract investors – that was how we envisioned raising the money needed for these trials. Those founding families are still recognised in the Abeona boardroom. It’s just a huge milestone for us to see that company being born and the clinical trials commence – and it’s as rare as the disease we were advocating for to see a business get its start like that!

It’s also just wonderful for us to see how advocacy has multiplied and grown over the years, and that the Sanfilippo community worldwide continues to gain strength and momentum.

So where is the money needed most at the moment? Probably not so much where there are biotech companies involved – they don’t need our money anymore – but there’s all kinds of new and exciting research out there that needs to include Sanfilippo. The likes of gene editing – has there been any specific research or clinical trials on how that can be applied to Sanfilippo?

Do you have any insights to share with industry cell & gene therapy developers who might be looking to engage with a patient advocacy group? What are the keys to a fruitful and long-standing partnership, in your view?

SW: Well, my opinion is that this picture is still evolving. But when one gets into issuing grants to – or signing off agreements with – a for-profit company, I think you need to relate it back to the funding of academic laboratories. We send out these application forms and they answer the questions, telling us specifically what they’re going to do with the money. They provide a budget showing where every single dime is to be spent, and we’re then given a report (twice a year, in our case) on how they have met their goals.

Now, you come to realise quickly when working with a company that it’s not a grant, it’s a contractual agreement. And at some point in time, you as a foundation have to revert back to doing the best you can on that contractual agreement to protect your assets, and all the hard work that we’ve spoken about in raising those funds. And not just what we do to raise those funds, but also the time it takes away from our children – as a family foundation, you never lose sight of the importance of that.

But at some point, it simply comes down to having faith in the integrity of your counterpart’s work. The person you’re dealing with on the other end of the phone, or across the desk – you have to believe they’re a person of integrity, a person of their word. Because truly, you’re not going to be able to get the same type of reporting out as you do from academic researchers. You have to find the companies – and people within those companies – that have the same mind-set you have. And nobody knows what a family such as mine or Elisabeth’s go through – the heartbreak we go through and the drive we have, because our love for our children is boundless.

I don’t know any other way of saying it: it’s a business deal, but as a foundation, that is the problem – the business is out to make money; we’re out to cure our children. You have to try and mesh that, and there is no contract in the world that any attorney can create that will give you that relationship. It really relates back to the basics of trusting the person or people within the company who realize above all that children’s lives are at stake.

EL: I would say good communication is first and foremost. You have to appreciate the position of foundations, charities – or families who have an affected child, in our case. And in that situation, answers from the company can’t come fast enough. When you’re putting the kind of energy and time and heart and soul into fundraising as we did, you also want to have some say in decision-making, know where research stands, and how funds are going to be used.

But as soon as a company becomes publicly traded, communication levels tend to change drastically. You tend to become just like everyone else, an investor. It’s very difficult for patient advocacy groups like ours to be involved in that type of business relationship, because we don’t necessarily get the answers we want when we want them. There’s information withheld from advocacy groups like ours for obvious reasons.

And that, I have to say, has been frustrating for groups like ours. Time is not on our side when it comes to having a child with a terminal illness. I think there has to be a lot of understanding, patience, trust and communication – those are probably four key words to keep in mind in order to work well together and move towards clinical trials and eventually, effective therapies.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial – NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.