Sleeping Beauty transposon vectors for therapeutic applications: advances and challenges

Cell Gene Therapy Insights 2017; 3(2), 131-158.

10.18609/cgti.2017.014

Transposable elements are natural, non-viral gene delivery vehicles capable of mediating stable genomic integration. The Sleeping Beauty (SB) transposon has the ability to cut-and-paste the ‘gene of interest’ into the genome, providing the basis for long-term, permanent transgene expression in transgenic cells and organisms. The SB transposon system is relatively well characterized, and has been extensively engineered for efficient gene delivery and gene discovery purposes in a wide range of vertebrates, including humans. The SB system is a safe and simple-to-use vector that enables cost-effective, rapid preparation of therapeutic doses of cell products. Recently, there has been a growing interest in using the SB system for therapy as evidenced by the large number of pre-clinical studies. SB moved swiftly from pre-clinical to clinical trials in almost a decade. In this article, we highlight the advancements and challenges associated with the SB system in various therapeutic applications. We also provide an overview that has been exploited by spin-off companies based on the SB system.

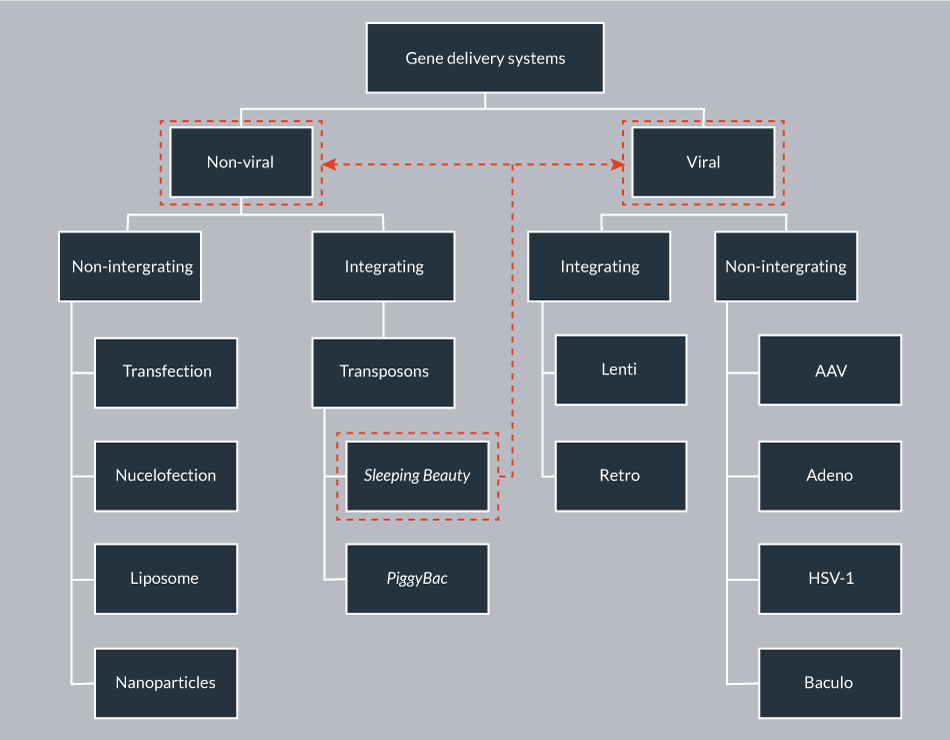

The high expectation on gene therapy continues to grow, as it holds the potential to provide a cure for myriad genetic diseases by substituting a corrupted gene with the respective functional one to achieve a therapeutic effect. The success of gene therapy is mainly dependent on the safety, efficacy, simplicity, cost-effectiveness and scalability of the vector system used for delivering and expressing the therapeutic gene of interest (GOI) into the cells. The numerous gene delivery approaches can be broadly classified as viral and non-viral mediated (Figure 1

In contrast to viral vectors, non-viral vectors have been considered for their simplicity, safety and ease of production. Non-viral approaches include physical or chemical delivery methods such as transfection, electroporation/nucleofection, gene gun and nanodelivery. The bottleneck problems of classical non-viral delivery are its low efficacy and transient nature. However, there are currently over 400 non-viral gene therapy clinical trials [1].

Mobile genetic elements (transposons) are natural gene delivery vehicles capable of genomic insertion. DNA transposons have the ability to transpose within the genome by a cut-and-paste process; however, this process can be restricted to a single excision event from a transfected plasmid to the genome. Stable genomic integration provides the basis for permanent transgene expression in transgenic cells and organisms, thereby addressing the bottleneck problem of classical non-viral delivery. Sleeping Beauty (SB) is a resurrected, synthetic transposon, belonging to the Tc1/mariner family of transposons that is active in a wide variety of vertebrates, including human cells [8,9]. The potential of the SB-based non-viral integrating system as an alternative to viral vectors has been thoroughly investigated in the last two decades. The studies demonstrated its ability to mediate long-term gene expression in various human cell types, and revealed several advantageous safety features. Currently, the SB transposon vector is the most widely used alternative gene carrier to integrating viral vectors.

The SB transposon system

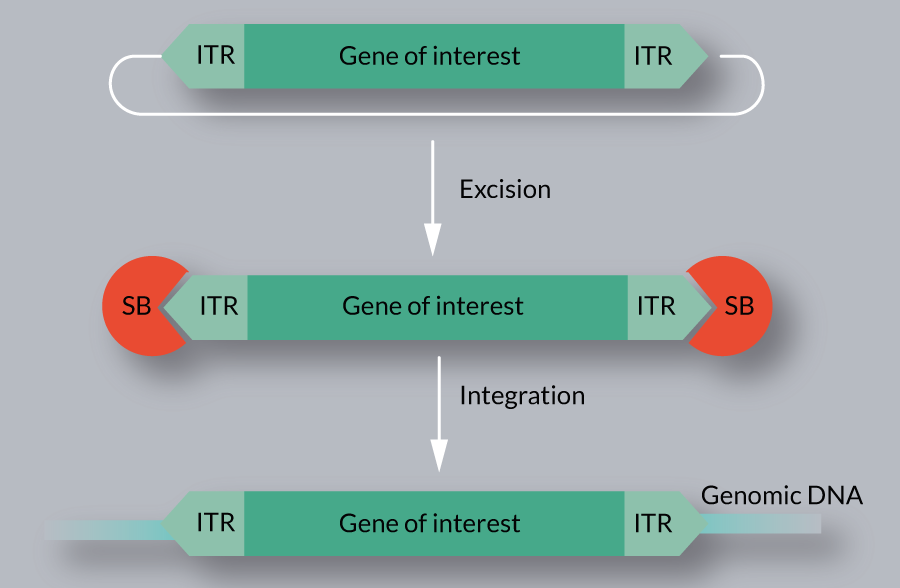

Generally a transposon system includes a transposon and a transposase. The transposon acts as a carrier, which carries the gene to be inserted into the genome. The transposase is the workhorse catalyzing the process of transposition. Naturally, the transposase is located between the inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) of the transposon. Importantly, however, the transposase gene can be replaced with any GOI, and the transposase can govern transposition events when encoded by a separate plasmid in trans. Physical separation of the transposon from the transposase enabled optimization of transposon versus transposase ratio, and also provided the freedom of supplying the transposase in the form of mRNA, instead of DNA [10]. Both components of the SB system, the transposon and the transposase, have been extensively engineered to improve transpositional activity.

Engineering the SB transposon

SB represents the first functionally active DNA transposon in vertebrates [8]. SB was engineered from ancient Tc1/mariner transposon fossils found within the Salmonid genomes by in vitro evolution [8]. The ITRs (230 bp) contains imperfect direct repeats (DRs) of 32 bp in length that serve as recognition signals for the transposase. Binding affinity and spacing between the DR elements within ITR has been crucial for efficient transpositional activities, suggesting that a constrained geometry is required during the pre-integration complex assembly [11,12]. Optimizing nucleotide residues (including mutations, deletions and additions) within the ITRs of the original SB transposon (pT) resulted in improved transposon versions, such as pT2, pT3, pT2B and pT4 (Table 1). For convenience of use, a whole series of transposon vectors with different reporter and selection markers are available [13].

| Table 1: List of currently available SB transposon vectors | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Transposon | Ref. |

| 1 | pT | [8] |

| 2 | pT2 | [11] |

| 3 | pT3 | [108] |

| 4 | pT2B | [15] |

| 5 | pT4 | [52] |

Engineering the SB transposase

The SB transposase is a 39 kDa protein that possess DNA binding domains, a nuclear localization signal (NLS) and the catalytic domain, featured by a conserved amino acid motif (DDE). Various screens mutagenizing the primary amino acid sequence of the SB transposase resulted in hyperactive transposase versions (Table 2). SB100X is 100-fold hyperactive compared to the originally resurrected transposase (SB10) in certain cell types [13,14].

| Table 2: List of currently available SB transposases | |

|---|---|

| Transposase | Ref. |

| SB10 | [8] |

| SB11 (3-fold higher than SB10) | [109] |

| SB12 (4-fold higher than SB10) | [66] |

| HSB1 – HSB5 (up to 10-fold higher than SB10) | [108] |

| HSB13 – HSB17 ( HSB17 is 17-fold higher than SB10) | [111] |

| SB100X (100-fold higher than SB10) | [14] |

| SB150X (130-fold higher than SB10) | [24] |

Mechanism of transposition

Transposition is a relatively well-characterized process, divided into excision and integration steps (Figure 2

Several host factors of SB transposition, including HMGXB4, HMGB1, BANF1, KU70 and MIZ-1 have been identified [16,17,25–27]. These factors physically interact with the SB transposase, and assist in different steps of the transposition reaction. In addition to host encoded cellular factors, certain conditions (e.g., serum starvation, DNA methylation) are reported to affect SB transposition [27,28].

Salient features of SB transposon technology

Since its establishment, the SB transposon technology has been exploited for various applications, including gene delivery and gene discovery in diverse species. Recently, it has been intensively exploited for human therapeutic applications. The SB technology exhibits several advantageous features:

- Non-viral: the GOI can be easily cloned between the ITRs of the transposon, which can be simply co-delivered with the transposase in the form of plasmids (or plasmid/mRNA). Such procedures can be performed in biosafety level 1 (BSL-1) laboratory, not requiring any complex biohazard containment facilities;

- Well-characterized: the transposition mechanism of the SB system and its interaction with the host is relatively well characterized;

- Economical: in comparison to the production cost of viral vectors, Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) grade plasmid production is relatively cheap, fast and less labor intense;

- Efficient and stable transgene expression: the hyperactive SB system has been demonstrated to support efficient and stable gene expression in various cell types. While the SB vector is not resistant to silencing (primarily dependent on the cargo), the expressed integration loci would faithfully produce the transgenic gene product long-term;

- Wide range of cell types: SB is capable of transposing in a wide variety of cell types, including therapeutically relevant primary cells [9];

- Not restricted to cycling cells: SB is able to transpose in non-dividing primary cells [29];

- Transgene integration is not restricted to efficient homologous recombination (HR): the transposase is capable of performing efficient transgene integration in cells, where the homologous recombination pathway of the host repair machinery is barely active;

- Maintains intact transgene structure: the SB vector is suitable to faithfully express complex transgenes;

- Cargo capacity: Although SB transposition is most optimal up to ~7.5 kb [9] of the transposon, the sandwich version (SA) has been shown to efficiently deliver cargos of >10 kb, thereby extending the cloning capacity of SB-based vectors. When combined with bacterial artificial chromosome (BACs), SB can deliver transgenes up to 100 kb [30];

- Unbiased, close-to-random integration profile: the close-to-random integration profile of SB was confirmed by multiple studies, and was reported from various organisms and cell types [20,23,24,31–35];

- Benign promoter/enhancer activity: the SB ITRs have negligible intrinsic promoter activity (less than ~100-fold vs MoMLV);

- Low immunogenicity: as the transposase is provided separately from the integrating transposon vector, it is present only temporarily in the cells. Thus, the non-viral transposon system generally does not trigger adverse immune responses that are observed with certain viral vectors (AV, AAV);

- No cross-mobilization in the human genome: None of the human genes are reported to recognize and mobilize the SB transposon (in contrast to the piggyBac [36,37]).

Current applications of SB transposon technology

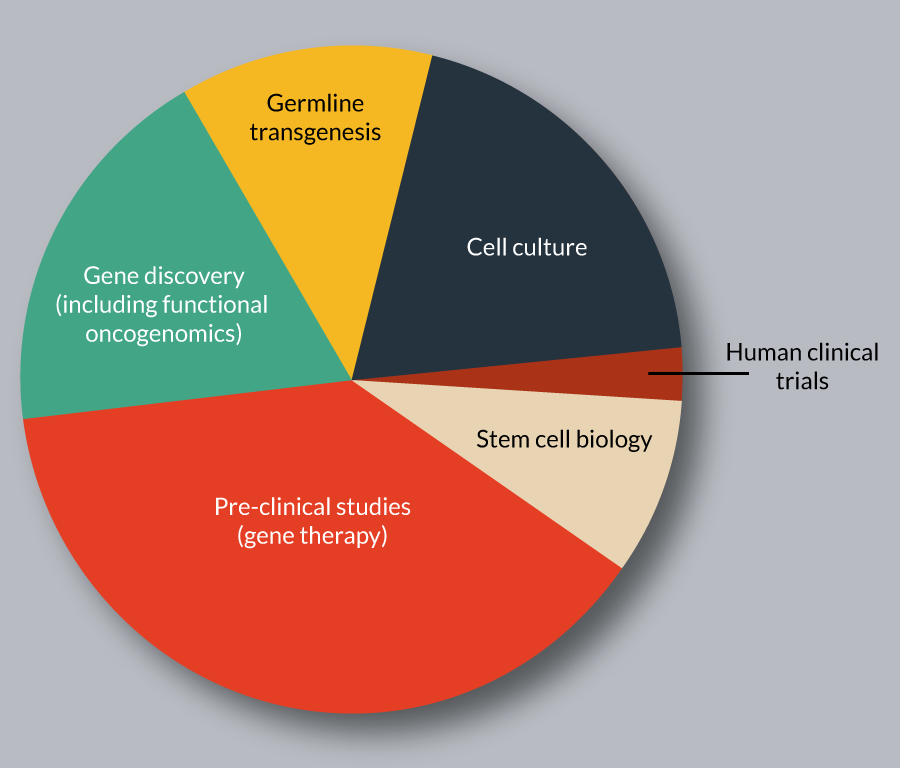

The SB transposon system has been used for diverse genetic applications in vertebrate species, which can be broadly classified as gene delivery and discovery (Figure 3

Tailoring the SB transposon technology for clinical applications

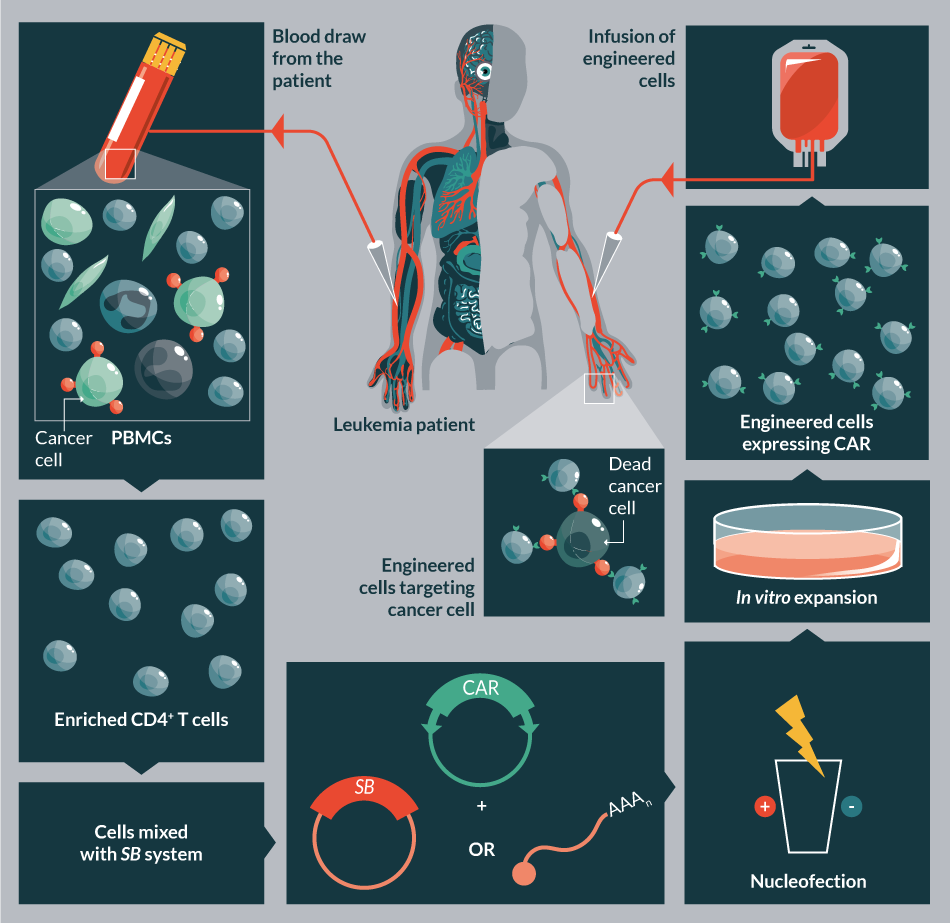

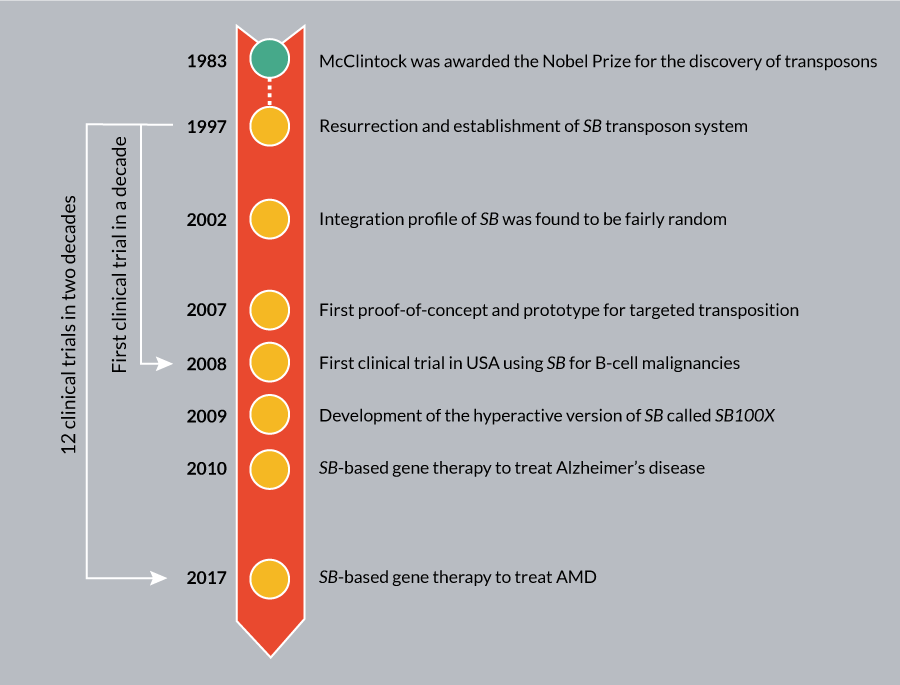

Here we provide an update on the cell and gene therapy applications. In the last decade, SB-based delivery vectors have been extensively used in pre-clinical animal models (for reviews see [38,60–63]). The encouraging pre-clinical results fueled its promotion towards clinical trials, and currently the technology is being evaluated to treat human diseases including cancer (lymphoma) (Figure 4

The hyperactive SB transposon system

The latest optimized version of the SB system comprises of the hyperactive SB100X transposase and the pT4 transposon [12,14]. The SB100X, generated by molecular evolutionary strategy performs with significantly higher efficiency of genomic integration that in certain cells is even comparable to viral performances [14]. Since SB100X can integrate the therapeutic gene more efficiently, relatively lower amounts of DNA are required to achieve similar results compared to the less hyperactive versions [64]. Importantly, protocols optimized for non-hyperactive transposase versions need to be re-optimized to avoid unnecessarily high number of integrated copies of the therapeutic gene. The hyperactive transposon version, pT4 has optimized substrate recognition [12].

Switch from DNA to mRNA as a source of transposase

Electroporation/nucleofection of plasmid DNA can be highly toxic to certain cells, including primary stem cells [64]. By contrast, nucleofection of RNA is not significantly more toxic than the nucleofection alone, indicating that the toxicity is not caused by nucleofecting nucleic acid per se. Thus, switching the transposase source from plasmid DNA to mRNA could mitigate the toxicity of the delivery. Furthermore, supplying the transposase as mRNA would ensure its transient expression, and decrease the risk of remobilization of the integrated therapeutic gene (safety concern) [10].

Extending the cloning capacity of the SB-based vector: the SA transposon

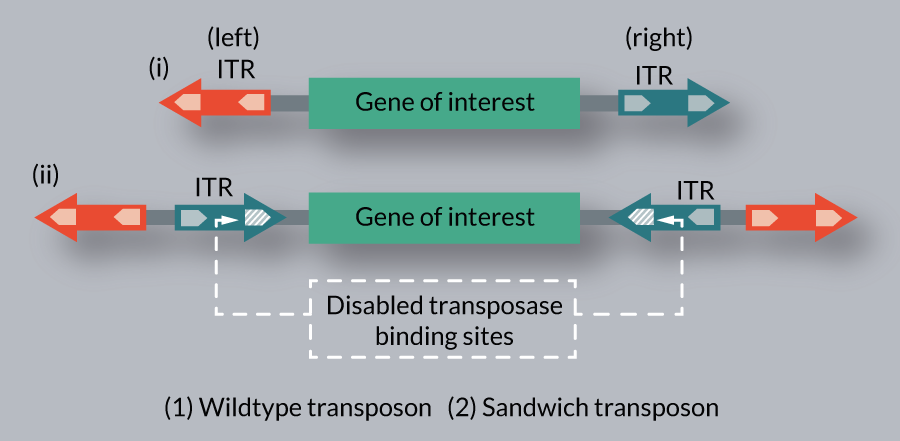

The transposition efficiency of SB is inversely correlated with the actual size of the transposon over 7.5 kb [9]. The ‘sandwich’ (SA) configuration of the transposon was aimed to improve the mobilization of larger cargos. The SA transposon consists of four ITRs in total, with two complete elements flanking the GOI in an inverted orientation (Figure 7

Shielding the transposon delivered transgene cassettes with insulators

SB facilitates the transgene expression in a copy-number dependent manner in transgenic animals, suggesting that the SB vector does not particularly alert the silencing machinery of the host [42]. Thus, incorporating insulator sequences in the SB-based vector might not be necessary to protect the transgene expression from silencing. On the other side, use of insulators motifs was demonstrated to effectively shield the promoter activity of the transgene cassette at the integration locus [26,68]. However, while insulators could prevent the transactivation of oncogenes, inserting insulator motifs could also have undesired effect on genome structure. Thus, the potential risks and benefits of using insulator sequences need to be carefully evaluated.

Delivery of the SB transposon system

Several non-viral gene delivery strategies have been tested for delivering SB constructs in vitro. In hard-to transfect cell types electroporation/nucleofection appears to be the most effective. A current limitation of this strategy for clinical applications is its capacity to engineer low number of cells. In principle, a flow through electroporation strategy could be beneficial to increase the number of engineered cells.

Besides nucleofection, nanoparticle-like carriers proved to be efficient to deliver the SB system. Notably, these carriers are also suitable to be combined with various targeting molecules that allow cell type specific transfer. In one example, hard-to-transfect mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) could be targeted with high efficacy (∼52%) by using engineered lipid-based nanoparticles (LBNs) encapsulating the SB system. These LBNs are chemically modulated to present synthetically reiterated MSC-targeting peptides on their surface [69]. Nanoparticle-like protocells with SB encapsulated inside can deliver the therapeutic gene into cancer cells, when folic acid is incorporated as a cancer cell-targeting motif [70]. Furthermore, special hepatocyte-targeted carriers, such as proteoliposomes containing galactose-terminated glycoproteins (e.g., the F protein of the Sendai virus) were demonstrated to effectively deliver the SB cargo into hepatocytes [71]. In a different approach, cell type-specific gene targeting using hyaluronan- and asialoorosomucoid-coated nanocapsules harboring the SB system were successfully used in vivo to direct genes to liver sinusoidal endothelial cells and hepatocytes, respectively [72]. Collectively, these studies imply that with the targeting ligand modification, the nanoparticle-like carriers can be developed as efficient gene delivery and targeting gene vehicles, highlighting their therapeutic potential.

Apart from the non-viral strategies, various SB-based viral hybrid technologies have been developed that can advantageously merge the excellent delivery properties of the viral vectors and the superior safety properties of the SB (Table 3 & Figure 8

| Table 3: List of various Sleeping Beauty -viral hybrid technologies. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid technology | Delivering vehicle | Integration machinery | Packaging capacity | Advantages | Ref. | |

| Adeno/ SB | Recombinant adenovirus | SB10 | up to 35 kb | Transduce dividing and non-dividing cells, and are one of the most efficient vehicles for in vivo gene delivery | [98] | |

| HCAdV/ SB | HCAdV | HSB5 | Up to 36 kb | Showed negligible toxicity in mice and canine model for hemophilia B. | [110] | |

| HCAdV/ SB | HCAdV | SB100X | Up to 36 kb | Lowest immunogenicity and toxicity compared to early generation adenoviral vectors | [74] | |

| AAV/ SB | Recombinant AAV | SB100X | Up to 5 kb | Stabilized transgene expression in combination with the high transduction efficiencies of AAV | [99] | |

| HSV-1 amplicon/ SB | HSV-1 | SB10 ; HSB5 ; SB12 | ≤130 kb | Efficient at delivering large transgenes to neurons specifically and provides stable long term expression | [100–103] | |

| Baculo/ SB | Baculovirus | SB11 | 38 kb | Stable long term expression | [104] | |

| IDLV/ SB | IDLV | SB10 ; SB11 ; HSB3 ; SB80X and SB100X | 8 kb | Un-biased random integration profile | [105] | |

| Adeno: Adenovirus; Baculo: Baculovirus; HCAdV: High-capacity adenoviral vector; AAV: Adeno associated virus); IDLV: Integrase defective lenti virus; HSV-1: herpes simplex virus 1 amplicon. | ||||||

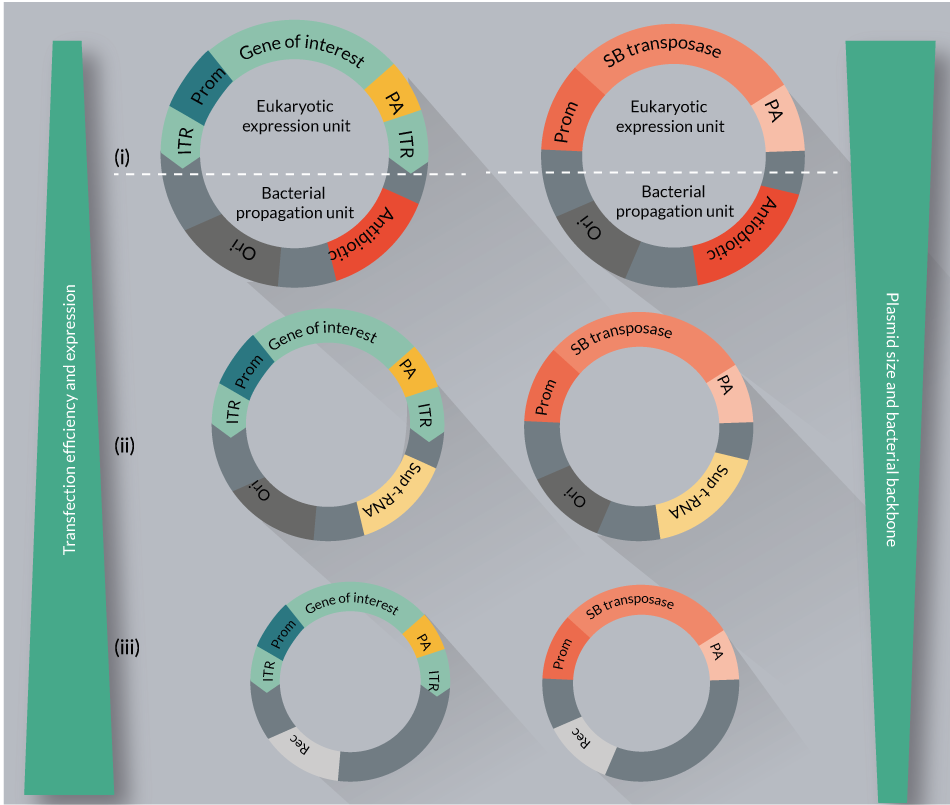

Eliminating bacterial sequences from the transposon vector

Non-viral delivery of large plasmid DNA molecules via electroporation is highly toxic to certain cell types, including primary T cells. Reducing the size of the DNA, and using supercoil DNA proved to be advantageous modifications in the delivery protocol [76,77]. Furthermore, the use of conventional plasmids as vectors that are propagated and isolated from bacteria raises a safety concern and a roadblock for broad clinical applications. In fact, the presence of bacterial backbone sequences on conventional plasmids such as antibiotic resistance gene and bacterial origin of replication has a number of negative consequences (Figure 9

The need to eliminate redundant bacterial backbone sequences motivated researcher’s to consider new approaches that reduces the size and bacterial sequence content of the plasmids. These efforts resulted in the development of plasmid free of antibiotic resistance (pFAR; see below and Figure 9ii) and minicircle (MC) vectors (Figure 9iii).

pFAR vectors are produced under selection pressure in a genetically modified E. coli, which contains an amber mutation in the thymidylate synthase gene. Introduction of pFAR plasmids having the suppressor transfer RNA gene (Sup t-RNA) into the mutant E. coli can restore normal growth, providing a selection pressure for the maintenance of pFAR miniplasmids. The pFAR miniplasmids are much more efficient (in transfection as well as expression in vitro and in vivo) compared to the conventional plasmids (Figure 9ii) [80]. Importantly, the pFAR and SB technologies were successfully combined [Johnen S, In press], and would be used in the clinical trial to treat AMD.

Minicircle DNA vectors represent small and supercoiled molecules that are devoid of any bacterial sequences, and contain almost exclusively the GOI. They are produced by the inclusion of site-specific intramolecular recombination motifs between the GOI and bacterial backbone in the parental plasmid. SB transposon and transposase minicircle constructs have been examined and optimized for safety and efficacy in various cell types [77], including primary T cells [76]. A minicircles-based SB system has been also used for efficient germline transgenesis [81]. Minicircle vectors seem to improve the transfection efficiency and transgene expression, while decreasing the toxicity associated with DNA delivery (Figure 9iii).

Collectively, miniplasmid vectors could be optimized for a variety of cell types, might meet future regulatory requirements for gene therapy and vaccine products, and set a new standard in advanced cellular and gene therapy.

Selection strategies for engineered cells expressing the gene of interest

Certain clinical applications require a large number of engineered cells. Thus, high efficacy of delivery and the frequency of therapeutic gene integration are crucial. In addition, it might be necessary to further enrich engineered cell cultures by using selective culturing protocols. Ideally, the selection period should be short. The following selection strategies have been tested for selecting genetically modified cells using the SB system.

In a cancer immunotherapy application, T cells are genetically modified by nucleofecting the SB system to express chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) that redirects specificity towards tumors. For example, CD19-specific CAR+ T cells could be selectively expanded on K562-derived artificial presenting cells (aAPC) co-expressing human CD19 and in the presence of an array of co-stimulatory molecules. Co-expression of CD19 serves to specifically propagate the genetically modified T cells, leaving those cells that did not integrate the transposon to die from neglect. This method of expansion strategy can efficiently overcome the toxicity of nucleofection and yield sufficient numbers of CD19- specific CAR+ T cells for clinical applications [82,83].

In an alternative protocol, administration of irradiated PBMCs was used to overcome cell death following SB-mediated gene transfer of CAR-modified cytokine-induced killer cells (CIKs). This clinical-grade protocol enables both robust gene transfer and efficient T cell expansion [84]. In addition, the SB transposon system has also been used for multiplexed gene transfer in conjugation with methotrexate selection. The strategy allows stable expression of up to three different transgenes in human CD4+ T cells [85].

Alternatively to cytotoxic drugs, a chemically responsive amplification mechanism can be used for selecting the engineered cells. A nearly pure population of stably transduced cells can be generated by non-viral delivery of desired transgenes through a combination of SB transposon-mediated integration and selective amplification using a chemically induced dimerizer (CID) [86]. This positive selection strategy is responsive to a small molecule trigger. Using this fast and efficient selection strategy, engineered cell populations with >98% purity could be obtained within 1 week. Dimerizer-induced cell growth could provide cost and reproducibility advantages to natural ligand stimulation in ex vivo cell culture, and could be used to control engineered cell behavior in vivo.

A ‘traceless selection system’ can efficiently select for engineered cells, and can be also used to select against cells that retain expression of the transposase gene. In this approach, the transposase is expressed together with a tractable fluorescent reporter. The strategy is based on the observation that upon co-transfection of both the transposase and transposon constructs, the presence of the transposase also reports on successful transposition events with high frequency. This concept could be used to produce highly enriched, auxiliary gene-free, cell products [87] that meet important safety requirements.

Regulation of the transgene expression

Transcriptional regulation could control the timing and dose of the expression of the therapeutic gene. In principle, the SB vector, possessing negligible enhancer/promoter activity on its own [26,88] can be easily adopted for transcriptional regulation. For regulated transgene expression ‘all-in-one’ TET SB vectors display a relatively low signal-to-noise ratio, resulting in regulatory windows of around 25,000-fold [89]. For safety concerns it is desirable to secure even elimination of the therapeutic gene. In conjunction with the SB system, thymidine kinase (TK) can be used for conditional ablation of the therapeutic construct [90].

Supporting protocols to monitor the safety and efficacy

- Following SB-mediated integration determining the copy number of the therapeutic gene is usually performed by PCR-based assays [13,91]. At very limited amounts of DNA droplet digital PCR can be successful to precisely determine the number of integrated vector copies;

- A high throughput integration site analysis belongs to the routinely performed safety studies. These analyses recover SB integration sites from the treated cells, and compare them to a computationally generated random genomic control [75]. SB exhibits a close-to-random integration profile with a small bias at repetitive elements [31]. The integration sites can be further investigated in various categories (e.g., library of safe harbor genomic sites, exons, regulatory regions, etc.) [35];

- A recently reported whole-body non-invasive imaging provides a method to examine long-term bio-distribution and persistence of the engineered cells. In this technology, bioluminescent imaging is used to monitor the signal emitted by firefly luciferase from the SB vector in vivo. The positron emission tomography (PET) is applied following injection of 2’-deoxy-2’-[18F]fluoro-5-ethyl-1-β-D-arabinofuranosyl-uracil ([18F]FEAU). Besides, monitoring safety, such a non-invasive imaging approach could be useful for assessing the efficacy of the therapeutic strategy [90].

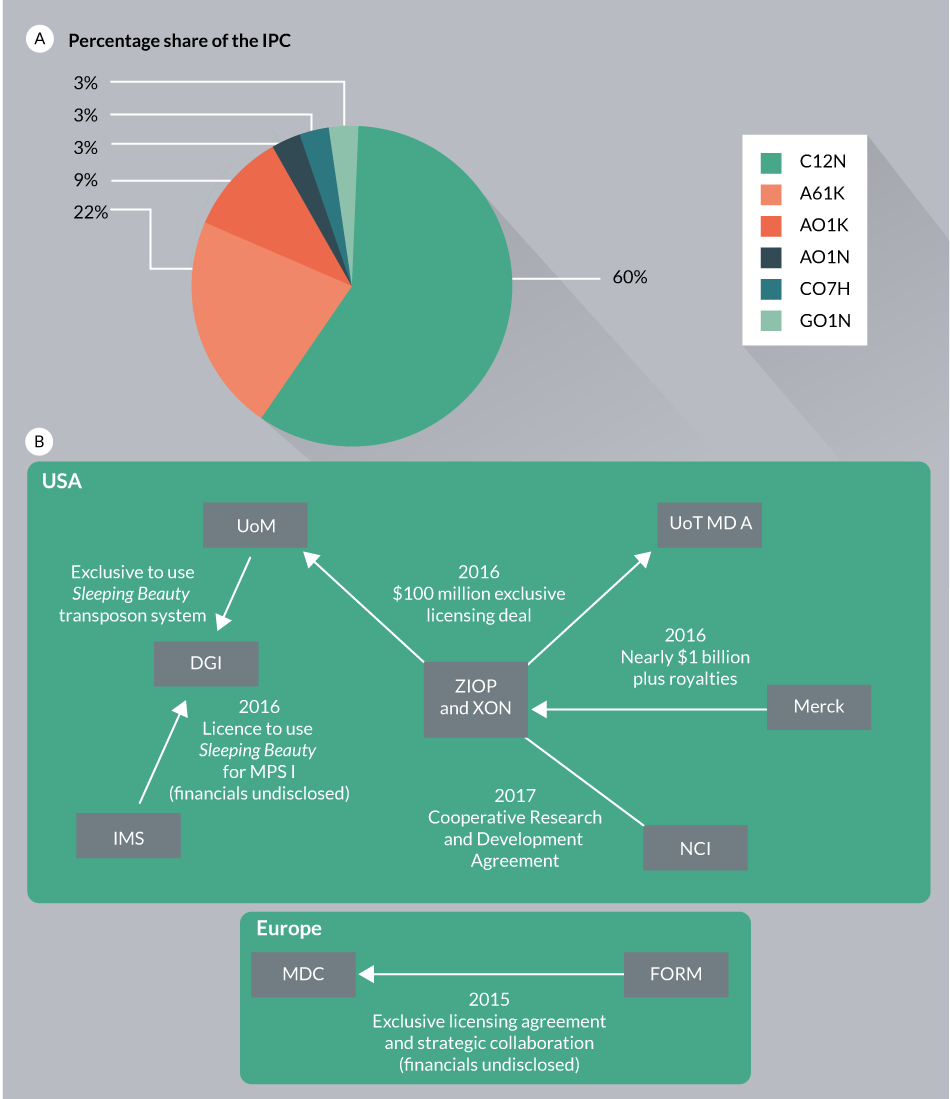

Clinical evaluation of SB transposon system/technology

Assignees for SB patent applications are associated with two leading organizations (University of Minnesota and the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC)). As discussed above (Figures 4–6), SB transposon technology applications span the cell and gene therapy industry market that has experienced rapid growth in the last few years (Table 4 & Figure 10

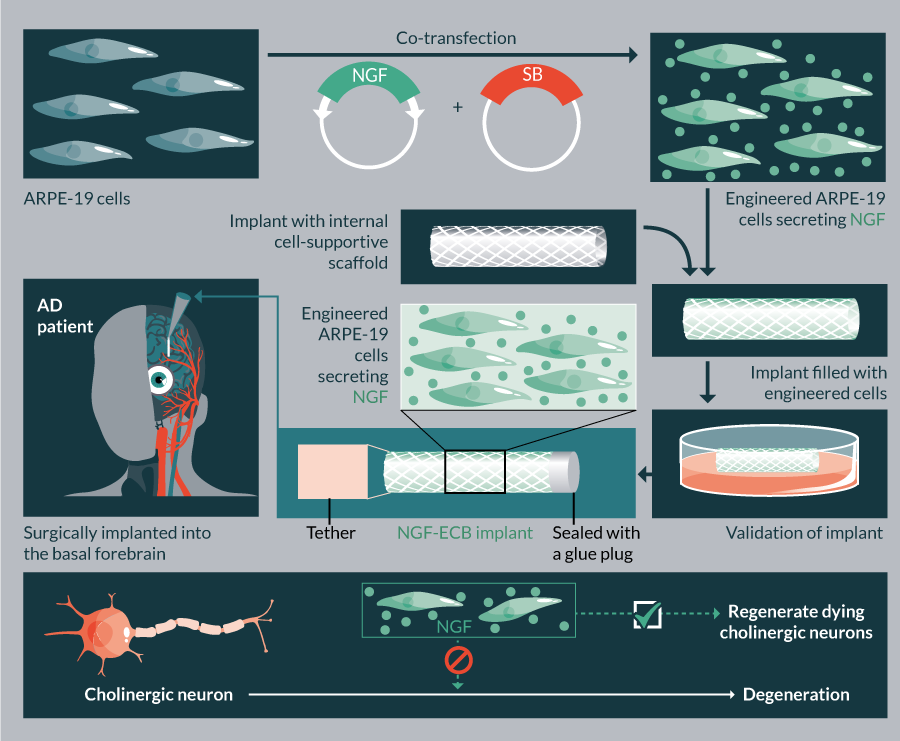

There are currently ten ongoing clinical trials in USA employing SB (Table 5). These trials use the SB11/pT2 version of the transposon system aiming to treat B-cell malignancies and metastatic breast cancer. In addition, the hyperactive SB100X-generated stable cell line in conjunction with Encapsulated Cell BiodeliveryTM was trialed to treat AD patients (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01163825) (Table 5). Another clinical trial is planned to launch in 2017, which would employ SB100X and pFAR technologies to treat AMD (TargetAMD [93]).

| Table 4: Industry interests in using Sleeping Beauty transposon technologies. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Company | Application | Area |

| Discovery Genomics, Inc. (DGI) | Gene therapy | Diseases of blood |

| B-MoGen Biotechnologies Inc. | Gene delivery and gene editing | Providing tools and custom services |

| Intrexon Corp. | Gene therapy | Cancer immunotherapy |

| Ziopharm Onclogy | Gene therapy | Cancer immunotherapy |

| Merck | Gene therapy | Cancer immunotherapy |

| Formula Pharmaceuticals, Inc. | Gene therapy | Cancer immunotherapy |

| Immusoft Corporation | Gene therapy | Rare diseases |

| NsGene A/S | Gene therapy | Neurological diseases (like Alzheimer’s disease, etc.) |

| Aldevron, LLC | Custom development and manufacturing services | Providing tools and custom services |

| Harborgen Biotechnologies, Inc. | DNA and related testing products development of precision medicine | Providing tools and custom services |

| Neuromics, Inc. | Bio-reagents company | Providing tools |

| Plasmid factory | Providing reagents and custom services | |

| Pharmead | Providing reagents and custom services | |

| The data presented in the table is obtained either based on the available information or by searching various online sources as of March 2017. Note that companies that have confidentially licensed the SB transposon technology are not listed in the presented table. | ||

Because of the significant complexities associated with cell engineering and therapy, partnerships tend to link different players, including academic research institutions and the biotech/pharma industries (Figure 10B). In one example, University of Minnesota has combined its patented SB-based gene delivery technology (SB11 and pT2) with intellectual properties of cancer therapies practiced by the University of Texas’ MD Anderson Cancer Center. This joint deal was meant to create the first-of-its kind non-viral immunotherapy treatment to support the patient’s immune system to fight against cancer. In an attempt to develop and evaluate the potential of immunotherapy to treat solid tumors, Intrexon and Ziopharm announced a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement (CRADA) with the National Cancer Institute (NCI). This join corporation will use T-cell receptors (TCRs) expressed by the non-viral SB system [94]. Recently, Immusoft acquired an exclusive access to use the SB transposon technology through acquisition of Discovery Genomics, Inc., which will be used for the development of autologous cell therapy products for treating a variety of diseases. Immusoft’s proprietary Immune System Programming (ISP™) technology would be used to program patients own B cells to generate miniature drug factories in the body. The Immusoft technology platform would use the SB transposon system for inserting genes encoding the correct human homolog of a missing or defective protein(s) to boost the patient’s own immune cells. Certain companies are providing reagents and custom services of SB transposon technology for research and clinical applications (Table 4).

| Table 5: List of currently ongoing clinical trials using Sleeping Beauty transposon system. | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sl. No | Clinical trial ID | Disease | Gene | Gene type | Cell source | Target cells | Gene delivery | Administration route | Clinical phase | Status | Year approved/ initiated |

| USA | |||||||||||

| 1 | US-0922 | CD 19+ B-lymphoid malignancies | CD19 Antigen Specific-Zeta T Cell Receptor | Receptor | Autologous | T lymphocytes | In vitro | Intravenous | I | open | 2008 |

| 2 | US-1003 | B-cell malignancies | CD19 Antigen Specific-Zeta T Cell Receptor | Receptor | Allogeneic | HLA Matched T Lymphocytes | In vitro | Intravenous | I | open | 2009 |

| 3 | US-1022 | B-cell malignancies | CD19 Antigen Specific-Zeta T Cell Receptor | Receptor | Allogeneic | Umbilical Cord Blood-derived Lymphocytes | In vitro | Intravenous | I | open | 2010 |

| 4 | US-1142 | B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia | CD19 Antigen Specific-Zeta T Cell Receptor | Receptor | Autologous | CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes | In vitro | Intravenous | I | open | 2012 |

| 5 | US-1192 | B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia | CD19 Antigen Specific-Zeta T Cell Receptor | Receptor | Autologous | CD4+and CD8+ T lymphocytes | In vitro | Intravenous | I | open | 2012 |

| 6 | US-1225 | B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia | CD19 Antigen Specific-Zeta T Cell Receptor | Receptor Others | Autologous | CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes | In vitro | Intravenous | I | open | 2013 |

| 7 | US-1236 | B-lineage malignancies | CD19 Antigen Specific-Zeta T Cell Receptor | Receptor | Allogeneic | Umbilical Cord Blood-derived Lymphocytes | In vitro | Intravenous | I | open | 2013 |

| 8 | US-1203 | B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia | CD19 Antigen Specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) CD3 zeta and CD137 Signaling | Receptor Others | Autologous | CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes | In vitro | Intravenous | I | open | 2013 |

| 9 | US-1353 | B-lineage malignancies | CD19 Antigen Specific-Zeta T Cell Receptor Interleukin-15 (IL-15) | Receptor Cytokine | Autologous | Primary CD3+ Lymphocytes | In vitro | Intravenous | I | open | 2014 |

| 10 | US-1360 | Metastatic breast cancer | Murine MUC1 Chimeric Antigen Receptor CD28/CD3 /OX40 Caspase 9 Interleukin-12 (IL-12) | Receptor antigen suicide Cytokine | Autologous | T Lymphocytes | In vitro | Intravenous | I/II | open | 2014 |

| Sweden | |||||||||||

| 11 | NCT01163825 | Alzheimer’s disease | NGF | Growth factor | Allogenic/ATCC | ARPE-19 | In vitro | Surgery | I | Unknown | 2010 |

| Switzerland | |||||||||||

| 12 | N.A | AMD | PEDF | Protein | Autologous | RPE | In vitro | Transplantation | Ib/IIa | U.R* | 2017** |

| The clinical trial data presented in the table is mined from the Journal of Gene Medicine database. AMD: Age-related macular degeneration; ARPE-19: Human retinal pigment epithelial cell line; ATCC: American type culture collection; N.A: Not available; NGF: Nerve growth factor; PEDF: Pigment epithelium-derived factor; RPE: Retinal pigment epithelial cells; U.R*: Under review by regulatory authorities. (http://www.abedia.com/wiley/vectors.php) and clinical trial database of National Institutes of Health (https://clinicaltrials.gov/) as of March 2017. **Clinical trials are anticipated to begin by the end of 2017. | |||||||||||

In an attempt to replicate the success of SB in therapeutic applications, MDC has established an exclusive licensing agreement and strategic collaboration with Formula Pharmaceuticals, Inc. for the development of Cytokine Induced Killer (C.I.K.) cell-based Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) immunotherapies. The collaboration platform is partially sponsored by the Helmholtz Association (MD-Cell, Innovation Lab), and would use MDC’s proprietaries, the hyperactive SB100X transposase and pT4 transposon, the optimized components of the SB transposon-based gene transfer system [95].

Translational insight

Despite periods of serious stagnation over the past few decades, the future of cell and gene therapy seems to be brighter. The turnaround began about a decade ago, and has been on an exponential trajectory by overcoming the early issues. Besides using traditional viral vectors, recent years have seen major breakthroughs in genome engineering systems, such as transposon-mediated gene delivery and CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing tools. As discussed above, SB appears to be a relative low risk and efficient gene delivery vector, and represents a safer alternative to integrating viral vectors. In parallel, rapid development occurred also in the CRISPR/Cas9 technology that can be developed for genome editing. These technologies became available in many species and have revolutionized genome engineering. These two approaches appear to have distinct features, and might occupy complementary niches in therapeutic applications. For example, due to its ability to specifically target sequences, the CRISPR/Cas9 system appears to be ideal for knocking out strategies. Currently it is tested in many pre-clinical studies, and could be on its way towards clinical applications in the near future. By contrast, although proof-of-concept studies exist to demonstrate that SB can be targeted to predetermined genomic loci [23,24], the current SB system is not suitable for flexible and efficient sequence-specific genome targeting. Nevertheless, among integrating gene delivery vectors the SB system has the highest chance of landing in a genomic safe harbor [35]. On the other side, today’s CRISPR/Cas9 strategies to manipulate large genomic regions (knocking in) face clear limitations for clinical translation. The current knock-in protocols are tightly dependent on homologous recombination of the cellular DNA repair machinery that has low activity in many clinically relevant cell types. Thus, compared to CRISPR/Cas9, the SB system is more suitable for applications that require ‘gene insertion’ (especially large genes). Regarding safety, the SB-mediated transgene integration is highly regulated and precise, and does not generate unspecific double stranded breaks in the genome (off target).

In addition to ex vivo applications, an important milestone in the SB technology is in vivo delivery. This gene transduction system is based on a hybrid transposon/adenovirus vector and the hyperactive SB transposase (SB100X) [74]. This in vivo strategy is effective and safe in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), and performs without the requirement of ex vivo expansion and transduction [75,96]. This system may overcome some of the current difficulties associated with cell collection and manufacturing, and provide technical advances for gene therapy. Collectively, the significant efforts invested in developing genome-engineering tools begin to pay dividends, as we witness an increasing interest in using them in various applications, including cell and gene therapy. The SB-mediated gene transfer is currently being evaluated in 12 clinical trials (Figure 11

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Dr Zoltan Ivics for his useful comments. ZI is supported by ERC Advanced Grant ERC-2011-AdG 294742-TRANSPOSOstress.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant financial involvement with an organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. SN and ZI are employees of the MDC. ZI has several patent applications on Sleeping Beauty. No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

1. Vectors used in gene therapy clinical trials: http://www.abedia.com/wiley/vectors.php

2. Thomas CE, Ehrhardt A, Kay MA. Progress and problems with the use of viral vectors for gene therapy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2003; 4: 346–58.

CrossRef

3. Hartman ZC, Appledorn DM, Amalfitano A. Adenovirus vector induced innate immune responses: impact upon efficacy and toxicity in gene therapy and vaccine applications. Virus Res. 2008; 132: 1–14.

CrossRef

4. Roe T, Reynolds TC, Yu G, Brown PO. Integration of murine leukemia virus DNA depends on mitosis. Embo J. 1993; 12: 2099–108.

5. Lewinski MK, Yamashita M, Emerman M et al. Retroviral DNA integration: viral and cellular determinants of target-site selection. PLoS Pathog. 2006; 2: e60.

CrossRef

6. Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Von Kalle C, Schmidt M et al. LMO2-associated clonal T cell proliferation in two patients after gene therapy for SCID-X1. Science 2003; 302: 415–9.

CrossRef

7. Baum C, von Kalle C, Staal FJ, Li Z et al. Chance or necessity? Insertional mutagenesis in gene therapy and its consequences. Mol. Ther. 2004; 9: 5–13.

CrossRef

8. Ivics Z, Hackett PB, Plasterk RH, Izsvak Z. Molecular reconstruction of Sleeping Beauty, a Tc1-like transposon from fish, and its transposition in human cells. Cell 1997; 91: 501–10.

CrossRef

9. Izsvak Z, Ivics Z, Plasterk RH. Sleeping Beauty, a wide host-range transposon vector for genetic transformation in vertebrates. J. Mol. Biol. 2000; 302: 93-102.

CrossRef

10. Wilber A, Wangensteen KJ, Chen Y et al. Messenger RNA as a source of transposase for sleeping beauty transposon-mediated correction of hereditary tyrosinemia type I. Mol. Ther. 2007; 15: 1280–7.

CrossRef

11. Cui Z, Geurts AM, Liu G et al. Structure-function analysis of the inverted terminal repeats of the sleeping beauty transposon. J. Mol. Biol. 2002; 318: 1221–35.

CrossRef

12. Wang Y, Pryputniewicz-Dobrinska D, Nagy EE et al. Regulated complex assembly safeguards the fidelity of Sleeping Beauty transposition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017 45: 311–326.

CrossRef

13. Kowarz E, Loscher D, Marschalek R. Optimized Sleeping Beauty transposons rapidly generate stable transgenic cell lines. Biotechnol. J. 2015; 10: 647–53.

CrossRef

14. Mates L, Chuah MK, Belay E et al. Molecular evolution of a novel hyperactive Sleeping Beauty transposase enables robust stable gene transfer in vertebrates. Nat. Genet. 2009; 41: 753–61.

CrossRef

15. Izsvak Z, Khare D, Behlke J et al. Involvement of a bifunctional, paired-like DNA-binding domain and a transpositional enhancer in Sleeping Beauty transposition. J. Biol. Chem. 2002; 277: 34581–8.

CrossRef

16. Izsvak Z, Stuwe EE, Fiedler D et al. Healing the wounds inflicted by sleeping beauty transposition by double-strand break repair in mammalian somatic cells. Mol Cell. 2004; 13: 279–90.

CrossRef

17. Wang Y, Wang J, Devaraj A et al. Suicidal autointegration of sleeping beauty and piggyBac transposons in eukaryotic cells. PLoS Genet. 2014; 10: e1004103.

CrossRef

18. Luo G, Ivics Z, Izsvak Z, Bradley A. Chromosomal transposition of a Tc1/mariner-like element in mouse embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 1998; 95: 10769–73.

CrossRef

19. Yant SR, Kay MA. Nonhomologous-end-joining factors regulate DNA repair fidelity during Sleeping Beauty element transposition in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003; 23: 8505–18.

CrossRef

20. Vigdal TJ, Kaufman CD, Izsvak Z et al. Common physical properties of DNA affecting target site selection of sleeping beauty and other Tc1/mariner transposable elements. J. Mol. Biol. 2002; 323: 441–52.

CrossRef

21. Ivics Z, Katzer A, Stuwe EE et al. Targeted Sleeping Beauty transposition in human cells. Mol. Ther. 2007; 15: 1137–44.

CrossRef

22. Yant SR, Huang Y, Akache B, Kay MA. Site-directed transposon integration in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007; 35: e50.

CrossRef

23. Ammar I, Gogol-Doring A, Miskey C et al. Retargeting transposon insertions by the adeno-associated virus Rep protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012; 40: 6693–712.

CrossRef

24. Voigt K, Gogol-Doring A, Miskey C et al. Retargeting sleeping beauty transposon insertions by engineered zinc finger DNA-binding domains. Mol. Ther. 2012; 20: 1852–62.

CrossRef

25. Zayed H, Izsvak Z, Khare D et al. The DNA-bending protein HMGB1 is a cellular cofactor of Sleeping Beauty transposition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003; 31: 2313–22.

CrossRef

26. Walisko O, Schorn A, Rolfs F et al. Transcriptional activities of the Sleeping Beauty transposon and shielding its genetic cargo with insulators. Mol. Ther. 2008; 16: 359–69.

CrossRef

27. Walisko O, Izsvak Z, Szabo K et al. Sleeping Beauty transposase modulates cell-cycle progression through interaction with Miz-1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 2006; 103: 4062–7.

CrossRef

28. Yusa K, Takeda J, Horie K. Enhancement of Sleeping Beauty transposition by CpG methylation: possible role of heterochromatin formation. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004; 24: 4004–18.

CrossRef

29. Huang X, Wilber AC, Bao L et al. Stable gene transfer and expression in human primary T cells by the Sleeping Beauty transposon system. Blood 2006; 107: 483–91.

CrossRef

30. Rostovskaya M, Fu J, Obst M et al. Transposon-mediated BAC transgenesis in human ES cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012; 40: e150.

CrossRef

31. Yant SR, Wu X, Huang Y et al. High-resolution genome-wide mapping of transposon integration in mammals. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005; 25: 2085–94.

CrossRef

32. Liu G, Geurts AM, Yae K et al. Target-site preferences of Sleeping Beauty transposons. J. Mol. Biol. 2005; 346: 161–73.

CrossRef

33. Geurts AM, Hackett CS, Bell JB et al. Structure-based prediction of insertion-site preferences of transposons into chromosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006; 34: 2803–11.

CrossRef

34. Huang X, Guo H, Tammana S et al. Gene transfer efficiency and genome-wide integration profiling of Sleeping Beauty, Tol2, and piggyBac transposons in human primary T cells. Mol. Ther. 2010; 18: 1803–13.

CrossRef

35. Gogol-Döring A, Ammar I, Gupta S et al. Genome-wide Profiling Reveals Remarkable Parallels Between Insertion Site Selection Properties of the MLV Retrovirus and the piggyBac Transposon in Primary Human CD4(+) T Cells. Mol. Ther. 2016; 24: 592–606.

CrossRef

36. Henssen AG, Henaff E, Jiang E et al. Genomic DNA transposition induced by human PGBD5. Elife 2015; 4.

CrossRef

37. Ivics Z. Endogenous Transposase Source in Human Cells Mobilizes piggyBac Transposons. Mol. Ther. 2016; 24: 851–4.

CrossRef

38. Ivics Z, Izsvak Z. The expanding universe of transposon technologies for gene and cell engineering. Mob. DNA 2010; 1: 25.

CrossRef

39. Wachter K, Kowarz E, Marschalek R. Functional characterisation of different MLL fusion proteins by using inducible Sleeping Beauty vectors. Cancer Lett. 2014; 352: 196–202.

CrossRef

40. Ammar I, Izsvak Z, Ivics Z. The Sleeping Beauty transposon toolbox. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012; 859: 229–40.

CrossRef

41. Narayanavari SA, Chilkunda SS, Ivics Z. Sleeping Beauty transposition: from biology to applications. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016; 1–27.

42. Katter K, Geurts AM, Hoffmann O et al. Transposon-mediated transgenesis, transgenic rescue, and tissue-specific gene expression in rodents and rabbits. FASEB J. 2013; 27: 930–41.

CrossRef

43. Alessio AP, Fili AE, Garrels W et al. Establishment of cell-based transposon-mediated transgenesis in cattle. Theriogenology 2016; 85: 1297–1311 e2.

44. Davis RP, Nemes C, Varga E et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human foetal fibroblasts using the Sleeping Beauty transposon gene delivery system. Differentiation 2013; 86: 30–7.

CrossRef

45. Grabundzija I, Wang J, Sebe A et al. Sleeping Beauty transposon-based system for cellular reprogramming and targeted gene insertion in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41: 1829–1847.

CrossRef

46. Kaji K, Norrby K, Paca A et al. Virus-free induction of pluripotency and subsequent excision of reprogramming factors. Nature 2009; 458: 771–5.

CrossRef

47. Fatima A, Ivanyuk D, Herms S et al. Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cell line from a patient with a long QT syndrome type 2. Stem Cell Res. 2016; 16: 304–7.

CrossRef

48. Kues WA, Herrmann D, Barg-Kues B et al. Derivation and characterization of sleeping beauty transposon-mediated porcine induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2013; 22: 124–35.

CrossRef

49. Muenthaisong S, Ujhelly O, Polgar Z et al. Generation of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells from different genetic backgrounds using Sleeping beauty transposon mediated gene transfer. Exp. Cell Res. 2012; 318: 2482–9.

CrossRef

50. Talluri TR, Kumar D, Glage S et al. Derivation and characterization of bovine induced pluripotent stem cells by transposon-mediated reprogramming. Cell Reprogram 2015; 17: 131–40.

CrossRef

51. Wang J, Xie G, Singh M et al. Primate-specific endogenous retrovirus-driven transcription defines naive-like stem cells. Nature 2014; 516: 405–9.

CrossRef

52. Wang J, Singh M, Sun C et al. Isolation and cultivation of naive-like human pluripotent stem cells based on HERVH expression. Nat. Protoc. 2016; 11: 327–46.

CrossRef

53. Keng VW, Yae K, Hayakawa T et al. Region-specific saturation germline mutagenesis in mice using the Sleeping Beauty transposon system. Nat. Methods 2005; 2: 763–9.

CrossRef

54. Izsvak Z, Ivics Z. Sleeping Beauty hits them all: transposon-mediated saturation mutagenesis in the mouse germline. Nat. Methods 2005; 2: 735–6.

CrossRef

55. Kokubu C, Horie K, Abe K et al. A transposon-based chromosomal engineering method to survey a large cis-regulatory landscape in mice. Nat. Genet. 2009; 41: 946–52.

CrossRef

56. Copeland NG, Jenkins NA. Harnessing transposons for cancer gene discovery. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010; 10: 696–706.

CrossRef

57. Moriarity BS, Largaespada DA. Sleeping Beauty transposon insertional mutagenesis based mouse models for cancer gene discovery. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2015; 30: 66–72.

CrossRef

58. Ruf S, Symmons O, Uslu VV et al. Large-scale analysis of the regulatory architecture of the mouse genome with a transposon-associated sensor. Nat. Genet. 2011; 43: 379–86.

CrossRef

59. Pindyurin AV, de Jong J, Akhtar W. TRIP through the chromatin: a high throughput exploration of enhancer regulatory landscapes. Genomics 2015; 106: 171–7.

CrossRef

60. Izsvak Z, Hackett PB, Cooper LJ. Translating Sleeping Beauty transposition into cellular therapies: victories and challenges. Bioessays 2010; 32: 756–67.

CrossRef

61. Hackett PB, Largaespada DA, Switzer KC. Evaluating risks of insertional mutagenesis by DNA transposons in gene therapy. Transl. Res. 2013; 161: 265–83.

CrossRef

62. Swierczek M, Izsvak Z, Ivics Z. The Sleeping Beauty transposon system for clinical applications. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2012; 12: 139–53.

CrossRef

63. Boehme P, Doerner J, Solanki M et al. The sleeping beauty transposon vector system for treatment of rare genetic diseases: an unrealized hope? Curr. Gene Ther. 2015; 15: 255–65.

CrossRef

64. Jin Z, Maiti S, Huls H, Singh H et al. The hyperactive Sleeping Beauty transposase SB100X improves the genetic modification of T cells to express a chimeric antigen receptor. Gene Ther. 2011; 18: 849–56.

CrossRef

65. Petrov DA, Schutzman JL, Hartl DL, Lozovskaya ER. Diverse transposable elements are mobilized in hybrid dysgenesis in Drosophila virilis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 1995; 92: 8050–4.

CrossRef

66. Zayed H, Izsvak Z, Walisko O, Ivics Z. Development of hyperactive sleeping beauty transposon vectors by mutational analysis. Mol. Ther. 2004; 9: 292–304.

CrossRef

67. Turchiano G, Latella MC, Gogol-Doring A et al. Genomic analysis of Sleeping Beauty transposon integration in human somatic cells. PLoS One 9: 2014; e112712.

CrossRef

68. Sharma N, Hollensen AK, Bak RO et al. The impact of cHS4 insulators on DNA transposon vector mobilization and silencing in retinal pigment epithelium cells. PLoS One 7: e48421.

CrossRef

69. Wang DD, Yang M, Zhu Y, Mao C. Reiterated Targeting Peptides on the Nanoparticle Surface Significantly Promote Targeted Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Gene Delivery to Stem Cells. Biomacromolecules 2015; 16: 3897–903.

CrossRef

70. Ma K, Fu D, Yu D et al. Targeted delivery of in situ PCR-amplified Sleeping Beauty transposon genes to cancer cells with lipid-based nanoparticle-like protocells. Biomaterials 2017; 121: 55–63.

CrossRef

71. Wang X, Mani P, Sarkar DP et al. Ex vivo gene transfer into hepatocytes. Methods Mol. Biol. 2009; 481: 117–40.

CrossRef

72. Kren BT, Unger GM, Sjeklocha L et al. Nanocapsule-delivered Sleeping Beauty mediates therapeutic Factor VIII expression in liver sinusoidal endothelial cells of hemophilia A mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2009; 119: 2086–99.

CrossRef

73. Yant SR, Ehrhardt A, Mikkelsen JG et al. Transposition from a gutless adeno-transposon vector stabilizes transgene expression in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002; 20: 999–1005.

CrossRef

74. Boehme P, Zhang W, Solanki M et al. A High-Capacity Adenoviral Hybrid Vector System Utilizing the Hyperactive Sleeping Beauty Transposase SB100X for Enhanced Integration. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2016; 5: e337.

CrossRef

75. Richter M, Saydaminova K, Yumul R et al. In vivo transduction of primitive hematopoietic stem cells after mobilization and intravenous injection of integrating adenovirus vectors. Blood 2016; 128: 2206–17.

CrossRef

76. Monjezi R, Miskey C, Gogishvili T et al. Enhanced CAR T-cell engineering using non-viral Sleeping Beauty transposition from minicircle vectors. Leukemia 2017; 31: 186–194.

CrossRef

77. Sharma N, Cai Y, Bak RO et al. Efficient sleeping beauty DNA transposition from DNA minicircles. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2013; 2: e74.

CrossRef

78. Simcikova M, Prather KL, Prazeres DM, Monteiro GA. Towards effective non-viral gene delivery vector. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 2015; 31: 82–107.

CrossRef

79. Tolmachov OE, Building mosaics of therapeutic plasmid gene vectors. Curr. Gene Ther. 2011; 11: 466–78.

CrossRef

80. Marie C, Vandermeulen G, Quiviger M et al. pFARs, plasmids free of antibiotic resistance markers, display high-level transgene expression in muscle, skin and tumour cells. J. Gene Med. 2010; 12: 323–32.

CrossRef

81. Garrels W, Talluri TR, Ziegler M et al. Cytoplasmic injection of murine zygotes with Sleeping Beauty transposon plasmids and minicircles results in the efficient generation of germline transgenic mice. Biotechnol. J. 2016; 11: 178–84.

CrossRef

82. Singh H, Figliola MJ, Dawson MJ et al. Reprogramming CD19-specific T cells with IL-21 signaling can improve adoptive immunotherapy of B-lineage malignancies. Cancer Res. 2011; 71: 3516–27.

CrossRef

83. Singh H, Manuri PR, Olivares S et al. Redirecting specificity of T-cell populations for CD19 using the Sleeping Beauty system. Cancer Res. 2008; 68: 2961–71.

CrossRef

84. Magnani CF, Turazzi N, Benedicenti F et al. Immunotherapy of acute leukemia by chimeric antigen receptor-modified lymphocytes using an improved Sleeping Beauty transposon platform. Oncotarget 2016; 7: 51581–97.

85. Kacherovsky N, Liu GW, Jensen MC, Pun SH. Multiplexed gene transfer to a human T-cell line by combining Sleeping Beauty transposon system with methotrexate selection. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2015; 112: 1429–36.

CrossRef

86. Kacherovsky N, Harkey MA, Blau CA et al. Combination of Sleeping Beauty transposition and chemically induced dimerization selection for robust production of engineered cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012; 40: e85.

CrossRef

87. Mezzadra R, Hollenstein A, Gomez-Eerland R, and Schumacher TN. A Traceless Selection: Counter-selection System That Allows Efficient Generation of Transposon and CRISPR-modified T-cell Products. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2016; 5: e298.

CrossRef

88. Moldt B, Yant SR, Andersen PR, Kay MA et al. Cis-acting gene regulatory activities in the terminal regions of sleeping beauty DNA transposon-based vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 2007; 18: 1193–204.

CrossRef

89. Heinz N, Schambach A, Galla M et al. Retroviral and transposon-based tet-regulated all-in-one vectors with reduced background expression and improved dynamic range. Hum. Gene Ther. 2011; 22: 166–76.

CrossRef

90. Najjar AM, Manuri PR, Olivares S et al. Imaging of Sleeping Beauty-Modified CD19-Specific T Cells Expressing HSV1-Thymidine Kinase by Positron Emission Tomography. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2016; 18: 838–848.

CrossRef

91. Kolacsek O, Pergel E, Varga N et al. Ct shift: A novel and accurate real-time PCR quantification model for direct comparison of different nucleic acid sequences and its application for transposon quantifications. Gene 2017; 598: 43–9.

CrossRef

92. PATENTSCOPE: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/search.jsf

93. TargetAMD: http://www.targetamd.eu

94. Intrexon press release: http://investors.dna.com/2017-01-10-ZIOPHARM-and-Intrexon-Announce-Cooperative-Research-and-Development-Agreement-with-the-National-Cancer-Institute-Utilizing-Sleeping-Beauty-System-to-Generate-T-cells-Targeting-Neoantigens

95. Ascenion GmbH press release: https://www.mdc-berlin.de/44841773/en/news/archive/2015/20150803-formula_pharmaceuticals_and_the_max_delbr_

96. Ren J, Stroncek DF. Gene therapy simplified. Blood 2016; 128: 2194–2195.

CrossRef

97. Merck KGaA forges a $941M CAR-T development deal with Intrexon: http://www.fiercebiotech.com/biotech/updated-merck-kgaa-forges-a-941m-car-t-development-deal-intrexon

98. Yant SR, Ehrhardt A, Mikkelsen JG, Meuse L, Pham T, Kay MATransposition from a gutless adeno-transposon vector stabilizes transgene expression in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002; 20, 999-1005.

CrossRef

99. Zhang W, Solanki M, Muther N et al. Hybrid adeno-associated viral vectors utilizing transposase-mediated somatic integration for stable transgene expression in human cells. PLoS One 2013; 8, e76771.

CrossRef

100. Bowers WJ, Mastrangelo MA, Howard DF, Southerland HA, Maguire-Zeiss KA, Federoff HJ. Neuronal precursor-restricted transduction via in utero CNS gene delivery of a novel bipartite HSV amplicon/transposase hybrid vector. Mol. Ther. 2006; 13, 580–8.

CrossRef

101. Peterson EB, Mastrangelo MA, Federoff HJ, Bowers WJ. Neuronal specificity of HSV/sleeping beauty amplicon transduction in utero is driven primarily by tropism and cell type composition. Mol. Ther. 2007; 15, 1848–55.

CrossRef

102. De Silva S, Mastrangelo MA, Lotta LT Jr, Burris CA, Federoff HJ, Bowers WJ. Extending the transposable payload limit of Sleeping Beauty (SB) using the Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV)/SB amplicon-vector platform. Gene Ther. 2010; 17, 424–31.

CrossRef

103. De Silva S, Mastrangelo MA, Lotta LT Jr et al. Herpes simplex virus/Sleeping Beauty vector-based embryonic gene transfer using the HSB5 mutant: loss of apparent transposition hyperactivity in vivo. Hum. Gene Ther. 2010; 21: 1603–13.

CrossRef

104. Luo WY, Shih YS, Hung CL et al. Development of the hybrid Sleeping Beauty-baculovirus vector for sustained gene expression and cancer therapy. Gene Ther. 2012; 19: 844–51.

CrossRef

105. Staunstrup NH, Moldt B, Mates L et al. Hybrid lentivirus-transposon vectors with a random integration profile in human cells. Mol. Ther. 2009; 17: 1205–14.

CrossRef

106. Intrexon, ZIOPHARM and MD Anderson in Exclusive CAR T Pact: http://investors.dna.com/2015-01-13-Intrexon-ZIOPHARM-and-MD-Anderson-in-Exclusive-CAR-T-Pact

107. Clinical trial database of National Institutes of Health: https://clinicaltrials.gov/

108. Yant SR, Park J, Huang Y, Mikkelsen JG, Kay MA. Mutational Analysis of the N-Terminal DNA-Binding Domain of Sleeping Beauty Transposase: Critical Residues for DNA Binding and Hyperactivity in Mammalian Cells. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004; 24: 9239-47.

CrossRef

109. Geurts AM, Yang Y, Clark KJ et al. Gene transfer into genomes of human cells by the sleeping beauty transposon system. Mol Ther. 2003; 8:108-17.

CrossRef

110. Hausl MA, Zhang W, Müther N et al. Hyperactive Sleeping Beauty Transposase Enables Persistent Phenotypic Correction in Mice and a Canine Model for Hemophilia B. Mol Ther. 2010; 18:1896-1906.

CrossRef

111. Baus J, Liu L, Heggestad AD, Sanz S, Fletcher BS. Hyperactive transposase mutants of the Sleeping Beauty transposon. Mol Ther. 2005; 12:1148-56.

CrossRef

Affiliations

Suneel A Narayanavari & Zsuzsanna Izsvák*

Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC), Berlin, Germany

* Author for correspondence: zizsvak@mdc-berlin.de

Submitted for review: Feb 21 2017 Published: Mar 30 2017

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial – NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.